The Phylloxera Plague of 1875 stands as one of the darkest chapters in the history of French viticulture. During the golden age of brandy production, the Cognac vineyards of the Charente countryside thrived, sustaining an empire of distillers and merchants who exported their liquid gold across the world. But in that fateful year, a silent invader changed everything. The phylloxera aphid, a microscopic insect native to North America, began attacking the roots of European grapevines, unleashing one of the greatest agricultural catastrophes ever recorded. Within a single decade, more than 85 percent of Cognac’s vineyards lay in ruin, leaving a region that once defined luxury on the edge of extinction.

The Arrival of a Tiny Invader

The story began around 1865, when phylloxera first appeared in southern France after unknowingly arriving with American vine cuttings used by French botanists. These insects fed on the roots of Vitis vinifera, the European grape species, creating wounds that led to rot and death. While the pest spread gradually through the Rhône and Bordeaux regions, it reached Cognac around 1872, taking only a few years to devastate the region’s fertile chalk soil.

By 1875, the once-thriving Cognac vineyards lay in ruin. Farmers watched their vines wither and die without understanding the cause. The plague spread through Charente and Charente-Maritime, the very heartlands of Cognac production. Merchants closed their warehouses, distilleries fell silent, and families who had tended vines for generations faced ruin. It was a catastrophe so complete that some believed the industry would never recover.

The Fall of a Global Spirit during the Phylloxera Plague of 1875

Before the Phylloxera Plague of 1875, Cognac stood as a global symbol of sophistication and artistry. Houses such as Hennessy, Martell, Rémy Martin, and Camus exported millions of bottles across Europe, Asia, and beyond, defining the essence of French refinement. The region’s prosperity depended entirely on the delicate balance of Ugni Blanc, Folle Blanche, and Colombard grapes, each essential to the spirit’s character. When the Phylloxera Plague of 1875 struck, that balance was destroyed. Entire families lost their livelihoods as the vines withered, and by 1880, production in the Charente region had collapsed by more than four-fifths, forcing many distilleries to close their doors.

Prices for brandy soared while quality declined, and merchants struggled to recreate the signature taste of true Cognac by blending surviving stocks with imported spirits. Yet none could match the depth and authenticity that defined the original vineyards. It was a period when centuries of craftsmanship and culture nearly vanished, and the identity of one of France’s greatest spirits hung by a thread.

The Search for a Cure to the Phylloxera Plague of 1875

As the Phylloxera Plague of 1875 spread across France, scientists and winegrowers launched an urgent search for a solution that could save the dying vineyards of Cognac. Early experiments with chemical treatments, flooding, and soil fumigation failed to stop the devastation. It was not until the 1880s that a breakthrough emerged when researchers such as Jules Émile Planchon and Charles Riley discovered that American grapevines possessed a natural resistance to the pest. By grafting European vines onto American rootstocks, growers found a way to preserve both the strength of resistant roots and the flavor integrity of traditional Cognac grapes. The discovery marked a turning point in the fight against the Phylloxera Plague of 1875, transforming crisis into innovation and saving an entire heritage from extinction.

It was a delicate balance between science and tradition. Many local growers resisted at first, fearing that grafted vines would compromise quality. Yet by 1890, the success of grafted vineyards had become undeniable. Replanting began across the Charente, and the rebirth of Cognac was underway. It would take more than thirty years for the region to fully recover, but the survival of the industry remains one of the most remarkable stories in agricultural history.

The Transformation of Cognac after the Phylloxera Plague of 1875

The Phylloxera Plague of 1875 permanently altered the landscape of Cognac and reshaped the future of the region’s craftsmanship. As vineyards were slowly replanted, growers turned toward the more resilient Ugni Blanc grape, known for its adaptability and steady yield. This decision created a lasting shift in the region’s viticulture, establishing Ugni Blanc as the dominant variety that continues to define Cognac production today. The crisis also led to the formation of viticultural cooperatives and research societies, uniting farmers, distillers, and scientists in the effort to safeguard their livelihoods and prevent another catastrophe.

Beyond recovery, the Phylloxera Plague inspired a renewed respect for terroir and tradition. Distillers began to prioritize quality, precision, and consistency, refining techniques of blending, barrel aging, and vineyard classification. From tragedy emerged a new generation of master blenders who transformed Cognac into a symbol of resilience, artistry, and enduring French heritage. Each bottle produced in the decades that followed carried not only the spirit of the vine but also the story of an industry reborn through perseverance.

The Legacy of Survival

The story of 1875 is not only about destruction but about rebirth. The phylloxera plague forced Cognac’s producers to reinvent their methods, creating the foundation for the modern industry. Today, the region’s 78,000 hectares of vineyards stand as a testament to endurance and adaptation. Each bottle of Cognac tells this hidden chapter of survival, where science and tradition united to preserve an irreplaceable art.

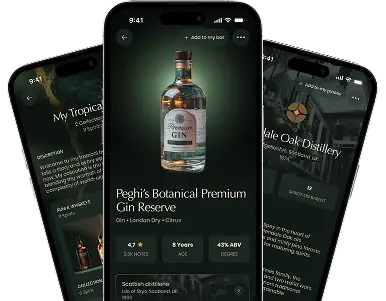

Where Barlist Meets the History of Craft

In the long history of spirits, few moments reveal as much about perseverance as the phylloxera crisis of Cognac. Barlist honors these stories not as mere history but as living lessons in craftsmanship and resilience. Every vineyard replanted, every bottle aged in oak, and every glass poured is a reminder that great spirits endure because passion never fades.