In the years following the Second World War, the Caribbean stood between preservation and progress. The islands, defined by centuries of rum-making heritage, were entering an age of industrial change that would reshape both their craft and their global identity. The year 1949 became a defining moment when distillers transitioned from pot stills to column stills, setting a new course for Caribbean Rum and its place in world spirits.

A New Era After War

When the war ended, the Caribbean economy faced uncertainty but also renewal. Rum remained one of the region’s most vital exports, yet many distilleries still relied on equipment and methods rooted in plantation-era traditions. The post-war reconstruction period brought investment, machinery, and modernization from abroad, offering the islands a new industrial path.

Governments encouraged innovation, and producers sought efficiency. Distilleries expanded with new ownership and larger operations, while engineers introduced continuous distillation systems capable of producing higher volumes with consistent quality. The arrival of column stills marked not just an upgrade but a transformation of purpose, turning artisanal rum into an international product ready for the modern age.

From Pot to Column

For centuries, the pot still defined Caribbean rum. This method produced spirits of rich body, deep molasses flavor, and strong identity. Each island developed its own profile through fermentation techniques and local climate, creating rums that were unmistakably distinct.

By 1949, however, global tastes had shifted. Drinkers were discovering lighter and cleaner spirits, suited for new cocktail culture in Havana, London, and New York. The column still, first developed in the nineteenth century, answered that call. It allowed continuous distillation, yielding higher proof spirits with a refined character. Caribbean producers quickly recognized that this was the path to larger export potential and broader appeal.

The Pioneers of Modern Rum

In Trinidad, the Caroni Distillery began leading the shift to column distillation to serve growing export demands. In Barbados, producers such as Mount Gay and West Indies Rum Distillery began balancing old and new techniques, using pot stills for character and column stills for smoothness.

Meanwhile, in Puerto Rico, the evolution became a revolution. The rise of Bacardi redefined the industry with a lighter, mixable rum designed for the new international palate. The combination of efficiency, clarity, and consistency became the hallmark of modern Caribbean Rum, transforming the region’s reputation from local craft to global authority.

Balancing Progress and Tradition

The adoption of column stills sparked debate among rum makers. Many feared that lighter rum styles might lose the individuality that defined Caribbean heritage. Traditionalists guarded the complexity and aroma that pot stills had always provided. Yet others saw potential in combining both methods, creating rums that captured the depth of tradition and the precision of progress.

Over time, this balance became the foundation of modern distilling across the region. Today, most renowned producers still blend pot-distilled richness with column-distilled finesse, crafting spirits that reflect both heritage and innovation in perfect measure.

Legacy of a Transformation

The year 1949 stands as a symbol of resilience and adaptation. The shift to column stills allowed the Caribbean to meet new global demand while preserving the essence of its culture. It created the diversity of style that defines the region today, from Jamaica’s bold pot rums to Barbados’s balanced blends and Puerto Rico’s refined exports.

This evolution did not erase history; it built upon it. Every bottle of Caribbean Rum today carries traces of that turning point — the moment when tradition and technology found common purpose in pursuit of excellence.

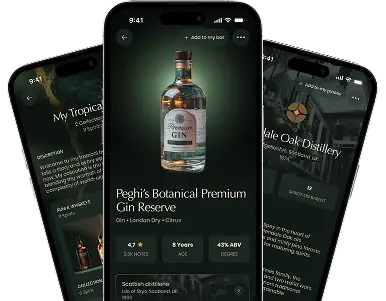

Where Barlist Meets the Heritage of Rum

Barlist celebrates this chapter as one of the great turning points in spirits history. The transformation from pot stills to columns represents not the loss of identity but the growth of craftsmanship. It shows how Caribbean distillers, faced with change, preserved authenticity while embracing the possibilities of modern production.

From Jamaica to Trinidad, from Barbados to Puerto Rico, the story of 1949 continues to define the rum world. It remains a testament to how innovation can honor heritage, proving that craftsmanship evolves, but its spirit endures.