The question – what is a distillery, reaches far beyond a physical location where alcohol is produced. A distillery is the point where geography, raw materials, regulation and human intent converge. It is where spirit identity is formed long before branding or bottling enters the picture. Every spirit category, whether whisky, rum, gin, brandy or agave-based spirits, owes its character to decisions made inside the distillery walls. Understanding what a distillery represents is essential to understanding why spirits taste the way they do and why certain names endure for generations.

The Distillery as the Origin of Spirit Character

At its most fundamental level, a distillery is the site where fermented material is transformed into distilled spirit. Yet this definition barely captures its influence. The distillery determines fermentation conditions, still design cut points and maturation philosophy. These choices shape texture, aroma and structure before any aging or blending takes place.

Historically, distilleries emerged where raw materials were abundant. Grain-based distilleries flourished in Scotland, Ireland and Eastern Europe. Sugarcane distilleries developed across the Caribbean and Latin America. Grape-based distilleries formed in France, Spain and Italy. This geographic alignment means that answering what is a distillery also means understanding place and agricultural context.

A distillery is not interchangeable. Its environment imposes constraints that define spirit identity.

Early Distilleries and the Formation of Regional Styles

Distilleries have existed in various forms since the Middle Ages. Written records from Europe document distillation activity as early as the 1100s, where monasteries and apothecaries distilled alcohol for medicinal use. By the 1500s, distillation expanded into commercial production, particularly in regions with surplus crops.

In Scotland, licensed distillation began formally after the Excise Act of 1823, which reshaped the whisky industry. Distilleries such as The Macalla, established in 1824, emerged during this period and helped define what Scotch whisky would become. Similar legal frameworks appeared elsewhere, shaping how distilleries operated and how spirits were classified.

These developments show that ‘what is a distillery’ cannot be separated from regulation. Law determines what may be distilled, how it is labeled and how identity is protected.

Still Design and Technical Identity

One of the most defining elements of a distillery is its stills. Pot stills, column stills and hybrid designs each produce spirits with distinct characteristics. Pot stills often yield heavier, more textured spirits, while column stills produce lighter, cleaner profiles.

The shape, size and configuration of stills influence reflux contact and alcohol purity. Many historic distilleries maintain still designs unchanged for decades because altering them would alter the spirit’s character. This technical continuity reinforces identity across generations.

Understanding what a distillery is requires recognizing that equipment is not neutral. It encodes flavor decisions into the spirit itself long before aging or blending occurs.

Fermentation Choices and House Style

Fermentation is often overlooked, yet it is one of the most powerful identity-shaping stages within a distillery. Yeast selection, fermentation length and temperature determine the formation of congeners that carry aroma and flavor through distillation.

Different distilleries develop recognizable house styles through fermentation alone. Some favor long fermentations that generate fruity esters, while others prioritize clean efficiency. These choices are rarely visible to consumers but they define how a spirit behaves during distillation and aging.

When asking what a distillery is, one must consider fermentation as a creative act rather than a mechanical step.

Maturation Philosophy and Environmental Influence

Many distilleries are defined by how they approach maturation. Climate warehouse design, cask selection and aging philosophy shape how spirit evolves over time. Distilleries in Scotland mature whisky slowly due to cooler climates while Caribbean rum distilleries experience rapid interaction between spirit and wood.

Warehouse location matters. Coastal distilleries often produce spirits with subtle maritime influence while inland distilleries develop different profiles. These environmental factors are inseparable from identity.

This is why spirits from the same category but different distilleries can taste profoundly different. A distillery is not simply where spirit is made but where time and environment interact deliberately.

Distillery Culture and Human Decision Making

Behind every distillery are people whose decisions shape identity. Master distillers, blenders and distillery teams maintain continuity while adapting to changing conditions. Oral tradition and institutional memory play a major role in preserving style.

Some distilleries operate with written protocols passed down for centuries, while others evolve through experimentation. Both approaches reinforce identity through intention rather than chance.

To understand – what is a distillery, fully is to recognize it as a living system shaped by human judgment as much as by equipment or geography.

Modern Distilleries and the Preservation of Identity

In the modern era, distilleries face pressure to scale production while preserving identity. Global demand has expanded markets but has also raised concerns about consistency and authenticity. Regulatory bodies and appellation systems now play critical roles in protecting distillery identity.

Craft distilleries emphasize transparency and locality while heritage distilleries focus on continuity. Both models depend on distillery-level decisions rather than branding alone.

Modern consumers increasingly seek distillery-specific spirits because they understand that identity begins at the source. This shift reinforces why the question what is a distillery remains central to spirit education today.

Distilleries as Cultural Landmarks

Beyond production, distilleries often become cultural landmarks. They anchor regional economies, preserve agricultural traditions and attract tourism. Distillery visits allow consumers to experience the physical context behind spirit identity.

In regions like Scotland, Kentucky Cognac and the Caribbean distilleries represent heritage as much as industry. They embody stories of migration, trade resilience and adaptation.

This cultural role elevates distilleries beyond manufacturing sites into guardians of tradition.

The Difference Between a Distillery and a Brewery

The difference between a distillery and a brewery is often misunderstood because both are places where alcohol is produced from fermented ingredients. Yet beyond this shared starting point, the two diverge fundamentally in process philosophy and cultural role. A distillery and a brewery do not simply produce different beverages. They represent distinct approaches to alcohol creation, each shaping identity, flavor and tradition in unique ways.

Best Distillery in The World

There’s no single « best » distillery, as it depends on your spirit preference (whisky, rum, gin) and criteria (tour, production, awards), but top contenders often include Scotland’s The Macallan & Glenfiddich (Scotch), Ireland’s Midleton (Irish Whiskey), Japan’s Suntory (Yamazaki/Hakushu), and USA’s Jack Daniel’s for iconic tours, while High Coast Distillery (Sweden) has won world’s best whisky awards recently.

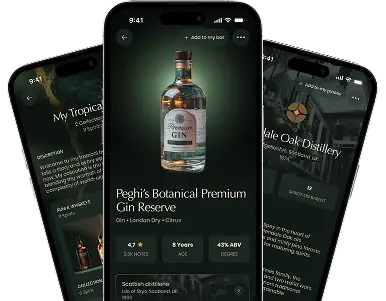

Where Barlist Meets Your Needs

Understanding what a distillery is unlocks a deeper appreciation for every spirit category. On Barlist distilleries are explored as origin points where identity is forged through place, process and people. By examining how distilleries define spirit character, Barlist connects drinkers to the foundations behind flavor reputation and heritage. A bottle tells a story but the distillery writes the first chapter and without it spirit’s identity would not exist.