A bit History of American Prohibition

On January 17, 1920, the United States went dry. With the ratification of the 18th Amendment and the passing of the Volstead Act, the manufacture, sale, and transport of alcoholic beverages became illegal across the country. It was the start of Prohibition, a 13-year constitutional experiment that aimed to cleanse the moral fabric of America. While the temperance movement celebrated a victory, what unfolded was far from purification. In fact, it marked one of the most transformative periods in the global history of spirits.

The story of Prohibition is often told in terms of gangsters, speakeasies, and bootleggers. Names like Al Capone and Lucky Luciano come to mind. Hidden jazz clubs. Bathtub gin. Corruption, violence, and a roaring black market. But behind the headlines, a quieter, international story was playing out, one that would profoundly impact distilleries from Scotland to Canada and reshape the course of the spirits industry worldwide.

Before the 1920s, the United States was one of the largest consumers of imported whisky. Scotch producers relied heavily on American drinkers to sustain their business. When Prohibition hit, many of Scotland’s distilleries faced an existential crisis. Export demand evaporated overnight. Some mothballed operations. Others turned to blending stock or shipping to alternative markets. A few bold players sought loopholes.

Sam Bronfman

One of them was Sam Bronfman, a Canadian entrepreneur whose family had fled anti-Jewish pogroms in Eastern Europe and settled in Saskatchewan. Bronfman founded Distillers Corporation Limited, and during Prohibition, he struck gold. Thanks to Canada’s proximity to the U.S. and its more lenient liquor laws, Bronfman legally exported vast quantities of Canadian whisky to the United States, ostensibly for medicinal purposes.

Pharmacies in the U.S. were permitted to sell whisky with a doctor’s prescription, and Bronfman’s whisky, shipped legally from Canada, was soon flowing into speakeasies and backroom bars. He wasn’t alone. Caribbean rum producers, Mexican mezcaleros, and European exporters all found creative ways to meet American thirst. Legal gray zones became billion-dollar arteries.

The effects of Prohibition rippled outward. In Ireland, where the industry was already faltering due to civil unrest and British trade barriers, the loss of American demand proved devastating. Dozens of Irish distilleries closed, never to reopen. Meanwhile, Scotch whisky, through sheer resilience and smarter export strategies, emerged from the era stronger, eventually dominating the global market by the mid-20th century.

One of the most remarkable consequences of the Prohibition era was the rise of the cocktail. Forced to mask the harsh flavors of low-quality or smuggled spirits, bartenders began creating drinks that were not just tolerable but enjoyable. This era gave birth, or at least widespread popularity, to classics like the Bee’s Knees, the Sidecar, and the Mary Pickford. Even the now-ubiquitous Old Fashioned and Manhattan gained renewed life underground.

Prohibition also professionalized the smuggling industry. Rum-runners like Bill McCoy became legends, known for delivering uncut, high-quality spirits, giving rise to the term “the real McCoy.” Bootleggers used modified speedboats, bribed customs agents, and mapped secret landing sites along the coasts. The sophistication of this black market would later influence organized crime for decades to come.

When Prohibition ended in 1933 with the 21st Amendment, the damage to the American spirits infrastructure was already done. Hundreds of distilleries had gone bankrupt. Skills were lost. Generational businesses had vanished. But on the international stage, new players had emerged, particularly Canadian, Caribbean, and Scottish producers who had adapted, survived, and even thrived.

Today, the legacy of Prohibition lingers not just in the mythology of the roaring twenties but in the structure of the spirits industry itself. The rise of multinational distribution, the resilience of Scotch whisky, and the global appeal of cocktails all trace their roots, in part, to this singular chapter in history.

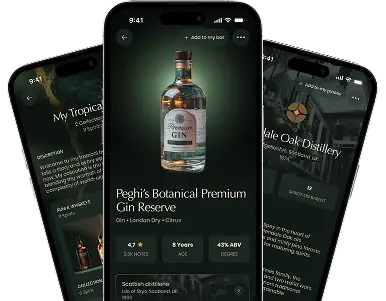

At Barlist, we believe in telling these stories because spirits are not just products. They are narratives, economies, migrations, and movements. The bottle in your hand may carry a legacy shaped by one of the most paradoxical laws in American history, a ban that fueled innovation, crime, culture, and ultimately, a global transformation.